Posted initially via The New York Times

Irish Repertory Theater’s Letters Series is a reminder: For sketching the arc of a relationship, nothing compares to intimate correspondence, our critic writes.

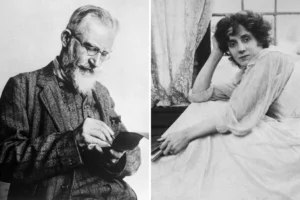

“Barbarous wretch: do you think I can live by imagination alone?” George Bernard Shaw groused in a 1913 letter to the actress Mrs. Patrick Campbell. Their yearslong correspondence is the subject of Jerome Kilty’s play “Dear Liar.” Credit…Universal Images Group, via Getty Images; Historical Picture Archive, via Getty Images

April 27, 2023

The playwright A.R. Gurney knew exactly what he was doing when he wrote “Love Letters,” a classic of the epistolary genre whose durability is due in no small part to its status as a magnet for celebrity casts.

As noted in the script, his 1988 play “needs no theater, no lengthy rehearsal, no special set, no memorization of lines, and no commitment from its two actors beyond the night of performance.” It simply requires actors to be side by side, reading letters aloud.

But choosing correspondence as a medium was awfully clever, too. It’s an inherently dramatic device — because a letter is both a vessel for self-expression and a catalyst for a response. Suspense swirls around what that response might be, and often whether one will arrive at all.

I confess to having a voracious appetite for other people’s mail, whether it’s read aloud onstage or inscribed in the pages of a book. For sketching the arc of a relationship, nothing compares to years’ worth of intimate correspondence.

Irish Repertory Theater’s Letters Series appeals to that predilection. Starting with Melissa Errico and David Staller in Jerome Kilty’s play “Dear Liar” (through Sunday), which is adapted from the decades-long exchange between George Bernard Shaw and the actress Mrs. Patrick Campbell, the series concludes with Matthew Broderick and Laura Benanti in “Love Letters” (May 30-June 3), whose Andrew Makepeace Ladd III and Melissa Gardner — friends since second grade — are fictional characters in the customary Gurney mold: white, Protestant, preppy.

“I’m writing because when I telephoned, you just hung up on me,” Andy scrawls to a miffed Melissa at some point in their college years. “One thing about letters: you can’t hang up on them.”

“You can tear up letters, though,” she snaps in reply. “Enclosed are the pieces.”

Gurney gives Melissa a sneaky kind of depth. An artistic child who comes of age in the 1950s, she morphs into an unhappy woman — a rebel manqué descended into substance abuse.

It’s jaw-dropping now to look at the roster of actresses who portrayed her in the original Broadway run of “Love Letters,” in 1989: among them Colleen Dewhurst, Swoosie Kurtz, Lynn Redgrave and Elaine Stritch. At the performance reviewed for The New York Times, Stockard Channing played Melissa.

In an era when substantial roles for women were significantly scarcer than they are now, Melissa got something like equal time with Andy over their half century of conversation — an advantage of the back-and-forth format that epistolary plays invite. Little wonder that boldface-name actresses were lining up.

The year before that, Charlotte Moore, Irish Rep’s artistic director, was among the actresses who played the role in the world-premiere production, at Long Wharf Theater in New Haven.

“Dear Liar,” which starred Brian Aherne and Katharine Cornell when it was first seen on Broadway in 1960, is the principal reason that people other than theater historians still know Campbell’s name, now forever linked with Shaw’s.

“Barbarous wretch: do you think I can live by imagination alone?” Shaw groused in a 1913 letter to Campbell, when she kept him waiting too long for a note. “Have you nothing to say to me?”

And Campbell, who would later be the first Eliza Doolittle in his “Pygmalion,” hit back at his prickly pedagogical tendencies reminiscent of Henry Higgins: “I have always been an odious letter writer — you have made me worse — grumbling that I can neither punctuate nor spell … you literary tradesman you!”

Theirs is a lively ink-on-paper conversation, but I am less enamored of it than of Shaw’s more thoughtful, and ultimately more heart-bruising, exchange with the actress Ellen Terry. Beginning in 1892, when he was a critic and fledgling playwright, it lasted for 30 years.

“Your letter makes me shriek with laughter,” Shaw wrote to her in 1899, “though I am in the worst of tempers.”

“I’m glad my scrawl made you ‘laugh,’” she replied promptly. “Your letter made my head spin …”

After her death in 1928, when a book of their correspondence came out, Shaw warned readers “not to judge it according to the code of manners which regulate polite letter writing in cathedral country towns.”

Given his penchant for flirting up a storm on the page — first with Terry, later with Campbell — he had a vested interest in contextualizing his own behavior, particularly because he was a married man. Temptingly, he explained that “the theater, behind the scenes, has an emotional freemasonry of its own, certainly franker and arguably wholesomer than the stiffness of suburban society outside.”

Which is precisely the allure of published correspondence: the promised glimpse of private selves having private chats — formidable cultural figures at their most down to earth. If Shaw had been all decorum, his letters and his plays would have been a snooze.

The foremost epistolary playwright of the current American theater has to be Sarah Ruhl, whose sublime romantic tragicomedy “Eurydice” (2003) is set in motion by a letter to the title character from her dead father in the underworld.

Eurydice joins him there, and then she too writes from the underworld, telling her husband, Orpheus: “I’ll give this letter to a worm. I hope he finds you.”

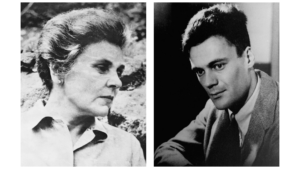

“All letter-writing is dangerous, anyway — fraught with peril,” the poet Elizabeth Bishop told Robert Lowell in 1962.Credit…Getty Images “There’s no one else I can quite talk to with confidence and abandon and delicacy,” Lowell wrote to Bishop in 1959.Credit…Associated Press

Any worthwhile correspondence is fueled by the desire, even the need, to reach across a yawning separation. That’s certainly true of “Words in Air,” the ferociously beautiful collected letters of the far-flung poets Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell, which Ruhl refashioned into her tantalizing 2012 play, “Dear Elizabeth.”

“I feel so forlorn without you, though this has been a happy year,” Lowell wrote to Bishop in 1959. “There’s no one else I can quite talk to with confidence and abandon and delicacy.”

But as Bishop knew, it can be anxious-making to speak the truth on paper and mail it off, not knowing how the recipient will take it. “All letter-writing is dangerous, anyway — fraught with peril,” she told Lowell in 1962.

Not the least of those perils is grief. This year brought the premiere of Ruhl’s intensely personal “Letters From Max, a Ritual,” a stage adaptation of “Letters From Max: A Book of Friendship,” the collection of her correspondence with Max Ritvo. A poet and former student of hers, he died in 2016, just four years after they met.

Mortality hangs over epistolary dramas in a way that other plays can more easily escape. A correspondence that spans years might have its intermittent sputters, but it finally ends for a reason, and often — as with nearly all of the pairs mentioned here — that reason is someone’s death or debility. The letters can then become a source of consolation: relics of a precious connection.

Letters, of course, can also be a kind of performance, especially when the authors have reason to believe that their words might be public someday. But a correspondence is an accumulation, and truth has a way of creeping in: what the writers mean to reveal about themselves, and what they don’t realize they’re letting slip.

We, their audience, see where they disappoint one another, where their friendships falter, where other people in their lives feel threatened by the bond they’ve forged. We see, too, where they love one another more desperately than they intended.

It’s all very dramatic. And so we lean in.